Loading...

Financial News

Latest in Financial News

Sigmanomics Market Recap and Forecast, Week of August 25 – 31, 2025

Following the significant drop in the equities market earlier this month (triggered by Trump’s announcement of renewed sweeping tariffs), the major indices—the S&P 500, the NASDAQ…

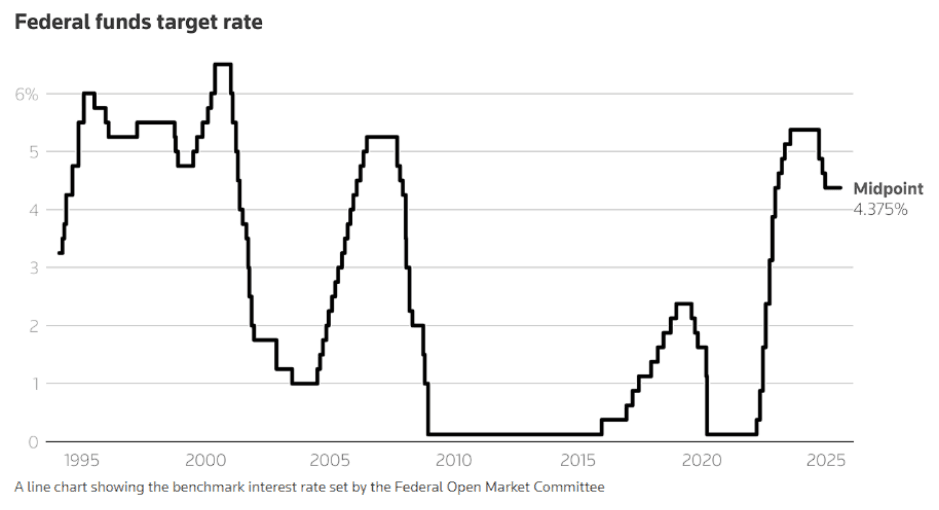

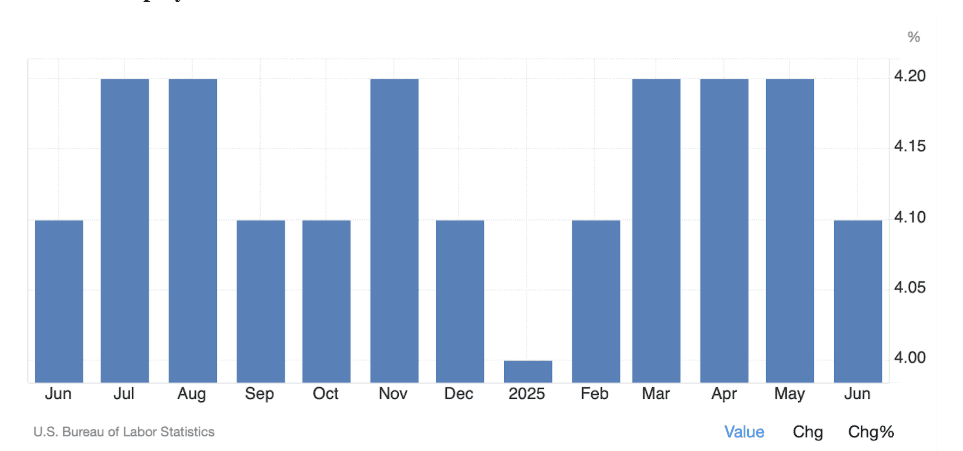

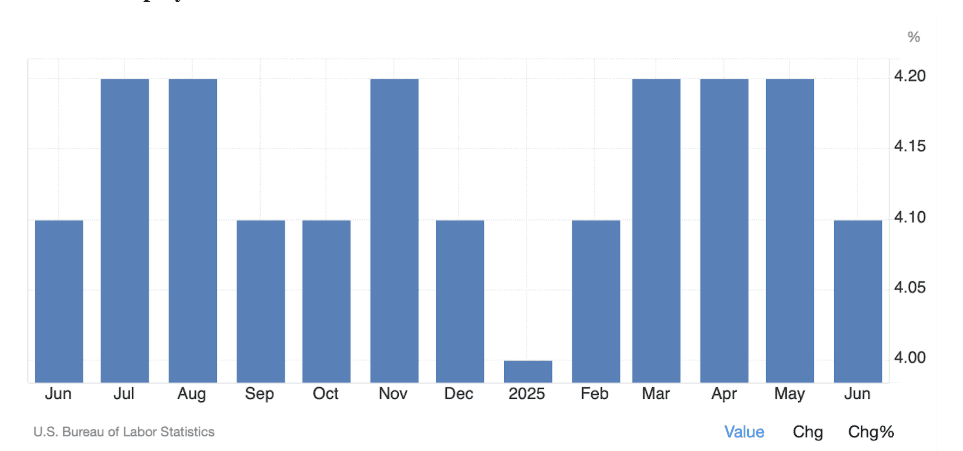

July CPI Report Strengthens Case for September Fed Cut

The Federal Reserve is once again at a crossroads. Inflation is cooling faster than expected, while growth signals are flashing mixed. July’s Consumer Price Index (CPI)…

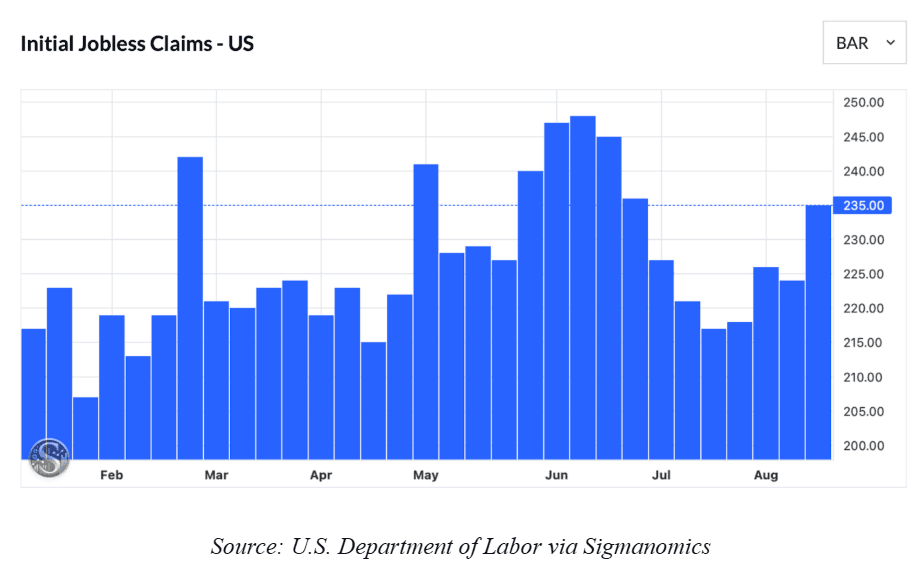

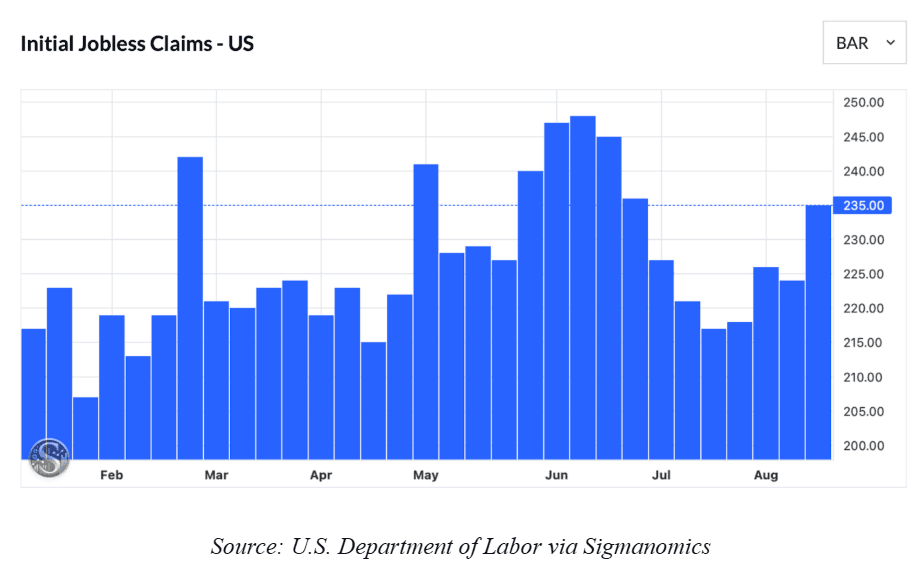

With Job Growth Faltering and Political Pressure Rising, Has the Fed Waited Too Long to Act?

The Federal Reserve is in a dilemma. Inflation is surging, but employment numbers are weak. For some time, the Fed has staved off pressure to cut…

Sigmanomics Market Commentary, Week of July 21 – 25, 2025

Summary The recently released June inflation data revealed a 0.3% month-over-month increase, up from 0.1% in May. This translates to a 2.7% year-over-year increase, fueling the…

Trump Raises Tariff Tensions: EU Sounds Alarm as 30% Duties on EU and Mexico Spark Inflation Concerns

Summary The latest threat of tariffs from US President Donald Trump has heightened concerns about inflation and trade disruptions. Trump has signaled a willingness to go…

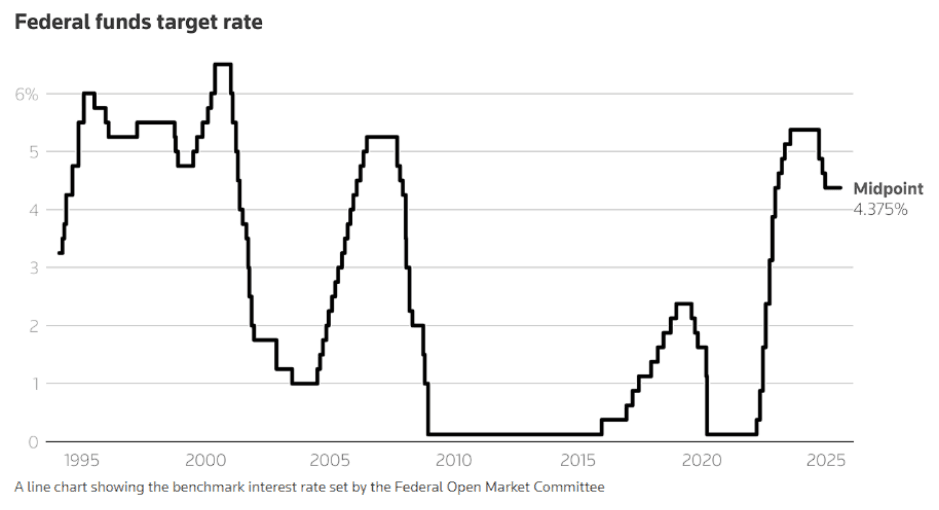

FOMC and U.S. Unemployment Data

Summary Table of Contents Marking the start of the second half of the year, the US economy and financial markets have renewed their bullish trajectory. Despite…

S&P 500 tests All Time Highs, RSI Divergence Provides Caution

New Highs or Reverse of Course? Table of Contents Wall street’s bounce back from its decline in April amid President Donald Trump on-again-off-again tariff salsa has…

Warner Bro. Discovery Splitting Streaming and Cable

In June 2025, Warner Brothers Discovery (WBD) announced plans separate companies with one company focusing on growing streaming, while the other dedicates to cable and global…

Global Trade Turmoil: Trump’s Tariff Threats Shake Markets, Housing, and Investor Confidence

Tariffs Shake the Markets In May 2025, the global economy faced a significant upheaval. Former President Donald Trump announced his plan to impose a 50% tariff…

Moody’s Shocks Markets: United States Downgraded Amid Uncertainty and Debt Concerns

Moody’s Investors Service, a top credit rating agency, recently downgraded the United States’ sovereign credit rating. This decision comes as the U.S. economy confronts several complex…

Trump’s Sweeping Tax Cut Plan Advances: What It Means for the U.S. Economy, Markets, and Your Wallet

Table of Contents The House Ways and Means Committee has officially approved the tax section of President Trump’s economic plan. This plan is often called the…

Meta’s $70 Billion AI Play: Can Zuckerberg’s Vision Pay Off by 2026?

Table of Contents Meta Platforms Inc. (META), the parent company overseeing popular social media platforms such as Instagram, WhatsApp, and Facebook, finds itself at a pivotal…

U.S. Secures $243 Billion in Landmark Deals with Qatar

Table of Contents On May 14, 2025, the White House said that President Donald Trump made deals with Qatar. These deals are worth over $243.5 billion.…

Microsoft to cut thousands of Employees: Focus on Restructuring and AI Innovation

Table of Contents As of May 2025, Microsoft Corporation (MSFT) is undergoing significant changes. This transformation shows its dedication to adapting its technology to meet the…

Trump’s Tariffs are Reshaping Global Trade and Shipping

Table of Contents The staggering costs of new tariffs imposed by the U.S. government are starting to be seen in global trade and shipping. Chinese imports…

Gold Prices Surge as Trade Wars Linger

Gold Prices Reach New Highs Table of Contents Gold prices hit a record high of $3,500.05 in April. They remain high due to geopolitical tensions, central…

Warren Buffet Retires at 94: How it will reshape Wall Street and Berkshire

Table of Contents Legendary Investor Announces Retirement Warren Buffet – The legendary CEO of Berkshire Hathaway is set to retire at the end of 2025. Succeeding…

Eurozone inflation rate remains unchanged in April 2025

Eurozone Consumer Prices Remain Unchanged Table of Contents Consumer prices in the Euro area remained unchanged at 2.2 percent in April 2025, beating economists forecasts of…

Possible U.S. and Japan Trade Deal in June 2025

Tariff Agreement on the Horizon? Table of Contents The Chief negotiator in Japan, Ryosei Akazawa expressed hopes of reaching a trade deal in June, 2025 on…

Mastercard Tops earnings Forecast as Consumers Spend more

Consumers Spend, Mastercard Earns Table of Contents First quarter earnings for Mastercard topped expectations, with the company reporting EPS of $3.73 versus analysts forecasts of $3.57,…

“Tariff Talks Near Conclusion” Trump Trade Chief Says

Tariff Deal Close? Table of Contents U.S. Trade Representative Jamieson Greer recently said that “we have deals that are close,” with reference to trade deal that…

S&P 500 extends 7 Day Gain

S&P Eyes Fibonacci Retracement Table of Contents The S&P 500 closed at 0.1% increase today with volume marking its highest level since April 24th. As short…

Sigmanomics Market Recap and Forecast, Week of August 25 – 31, 2025

Following the significant drop in the equities market earlier this month (triggered by Trump’s announcement of renewed sweeping tariffs), the major indices—the S&P 500, the NASDAQ…

July CPI Report Strengthens Case for September Fed Cut

The Federal Reserve is once again at a crossroads. Inflation is cooling faster than expected, while growth signals are flashing mixed. July’s Consumer Price Index (CPI)…

With Job Growth Faltering and Political Pressure Rising, Has the Fed Waited Too Long to Act?

The Federal Reserve is in a dilemma. Inflation is surging, but employment numbers are weak. For some time, the Fed has staved off pressure to cut…

Sigmanomics Market Commentary, Week of July 21 – 25, 2025

Summary The recently released June inflation data revealed a 0.3% month-over-month increase, up from 0.1% in May. This translates to a 2.7% year-over-year increase, fueling the…

Trump Raises Tariff Tensions: EU Sounds Alarm as 30% Duties on EU and Mexico Spark Inflation Concerns

Summary The latest threat of tariffs from US President Donald Trump has heightened concerns about inflation and trade disruptions. Trump has signaled a willingness to go…

FOMC and U.S. Unemployment Data

Summary Table of Contents Marking the start of the second half of the year, the US economy and financial markets have renewed their bullish trajectory. Despite…

S&P 500 tests All Time Highs, RSI Divergence Provides Caution

New Highs or Reverse of Course? Table of Contents Wall street’s bounce back from its decline in April amid President Donald Trump on-again-off-again tariff salsa has…

Warner Bro. Discovery Splitting Streaming and Cable

In June 2025, Warner Brothers Discovery (WBD) announced plans separate companies with one company focusing on growing streaming, while the other dedicates to cable and global…

Global Trade Turmoil: Trump’s Tariff Threats Shake Markets, Housing, and Investor Confidence

Tariffs Shake the Markets In May 2025, the global economy faced a significant upheaval. Former President Donald Trump announced his plan to impose a 50% tariff…

Moody’s Shocks Markets: United States Downgraded Amid Uncertainty and Debt Concerns

Moody’s Investors Service, a top credit rating agency, recently downgraded the United States’ sovereign credit rating. This decision comes as the U.S. economy confronts several complex…

Trump’s Sweeping Tax Cut Plan Advances: What It Means for the U.S. Economy, Markets, and Your Wallet

Table of Contents The House Ways and Means Committee has officially approved the tax section of President Trump’s economic plan. This plan is often called the…

Meta’s $70 Billion AI Play: Can Zuckerberg’s Vision Pay Off by 2026?

Table of Contents Meta Platforms Inc. (META), the parent company overseeing popular social media platforms such as Instagram, WhatsApp, and Facebook, finds itself at a pivotal…

U.S. Secures $243 Billion in Landmark Deals with Qatar

Table of Contents On May 14, 2025, the White House said that President Donald Trump made deals with Qatar. These deals are worth over $243.5 billion.…

Microsoft to cut thousands of Employees: Focus on Restructuring and AI Innovation

Table of Contents As of May 2025, Microsoft Corporation (MSFT) is undergoing significant changes. This transformation shows its dedication to adapting its technology to meet the…

Trump’s Tariffs are Reshaping Global Trade and Shipping

Table of Contents The staggering costs of new tariffs imposed by the U.S. government are starting to be seen in global trade and shipping. Chinese imports…

Gold Prices Surge as Trade Wars Linger

Gold Prices Reach New Highs Table of Contents Gold prices hit a record high of $3,500.05 in April. They remain high due to geopolitical tensions, central…

Warren Buffet Retires at 94: How it will reshape Wall Street and Berkshire

Table of Contents Legendary Investor Announces Retirement Warren Buffet – The legendary CEO of Berkshire Hathaway is set to retire at the end of 2025. Succeeding…

Eurozone inflation rate remains unchanged in April 2025

Eurozone Consumer Prices Remain Unchanged Table of Contents Consumer prices in the Euro area remained unchanged at 2.2 percent in April 2025, beating economists forecasts of…

Possible U.S. and Japan Trade Deal in June 2025

Tariff Agreement on the Horizon? Table of Contents The Chief negotiator in Japan, Ryosei Akazawa expressed hopes of reaching a trade deal in June, 2025 on…

Mastercard Tops earnings Forecast as Consumers Spend more

Consumers Spend, Mastercard Earns Table of Contents First quarter earnings for Mastercard topped expectations, with the company reporting EPS of $3.73 versus analysts forecasts of $3.57,…