S&P 500 Hits Fresh Record High Before Tech Sell-off as Rally Shows Signs of Fatigue

The S&P 500 just notched an all-time high, a trend that seems not to let up this year. But for the second time in two weeks, the index quickly retreated. Inflation jitters undid the first peak, and this latest retreat comes down to tech fatigue. The question on investors’ minds now is whether this phenomenon is a healthy pause or the start of a deeper correction.

The Record High and Tech Sell-off

On August 28, the S&P 500 closed at 6,501.86, the highest level in history. The level was also 10.55% higher than on December 31, 2024 (year-to-date), and a massive 30.99% recovery from the April 8 slump.

Comparatively, the Dow only gained 7.27% YTD and recouped 21.23% from the April 8 nosedive. The tech-heavy Nasdaq Composite, on the other hand, was up 12.40% YTD and up 42.16% from April 8. In other words, the August 28 record wasn’t a broad-market celebration; it was a tech-led parade.

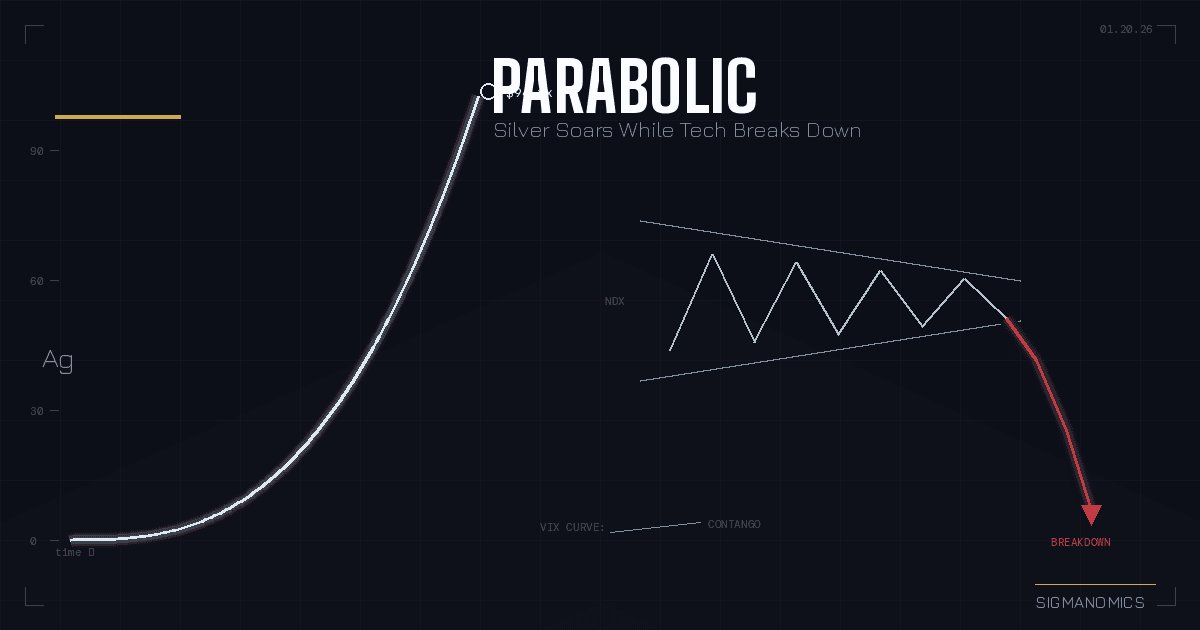

Figure 1: S&P 500 vs Nasdaq (August 26 – September 2, 2025), Image Source: Sigmanomics

Figure 1: S&P 500 vs Nasdaq (August 26 – September 2, 2025), Image Source: Sigmanomics

For context, on April 8, the market experienced its sharpest slump in years as investors reacted to sweeping new tariffs. On April 2, President Trump announced 10% tariffs on nearly all imported goods, plus higher “reciprocal tariffs” targeting countries with trade surpluses against the US. A week later, the S&P 500 had plunged 19% from its February peak, nearly breaching bear market territory.

But the market has hit at least five distinct record closing highs since then. And tech stocks were a key driver in three separate events (see the table below).

|

Date |

Closing Value |

Notable Driver |

|

August 28, 2025 |

6,501.86 |

Strong GDP, Fed optimism, tech surge |

|

August 14, 2025 |

6,389.45 |

Mega-cap tech rally |

|

July 3, 2025 |

6,279.35 |

Jobs report beat forecasts |

|

June 30, 2025 |

6,204.95 |

Trade tensions eased |

|

June 27, 2025 |

6,173.07 |

AI boom and chip sector momentum |

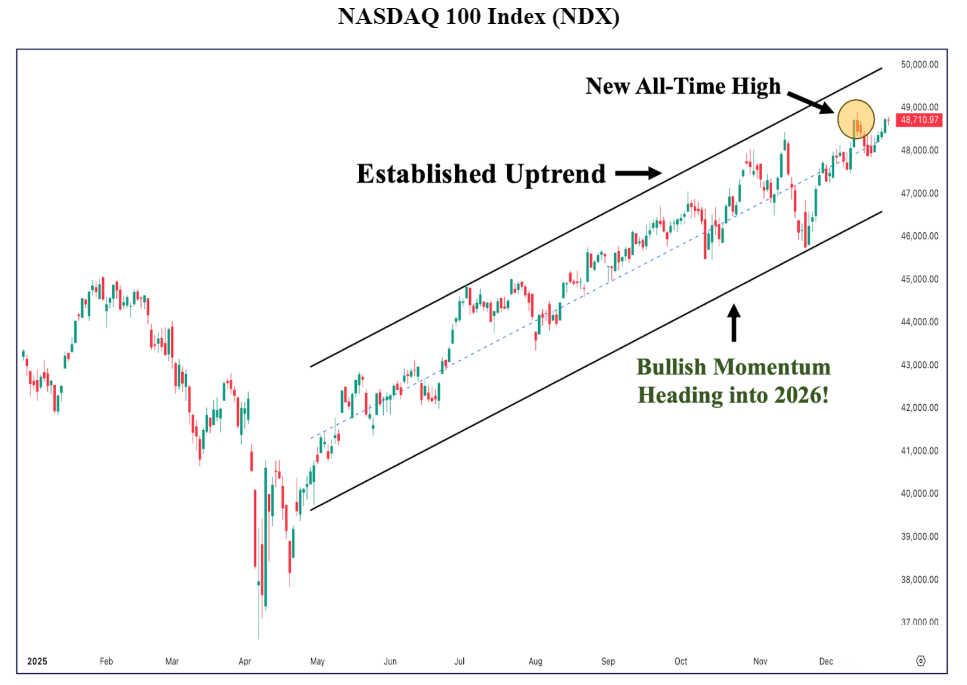

Market Breadth Concerns

As of August 29, Nvidia alone accounted for 7.3% of the S&P 500 – equal in weight to the smallest 231 companies put together. And the seven tech giants (dubbed the “Magnificent 7”) (Tesla, Apple, Alphabet, Amazon, Meta Platforms, Nvidia, and Microsoft) now make up one-third of the index’s market capitalization. Including other top-heavy names, the top 10 stocks were responsible for nearly 40% of the index’s value.

This phenomenon raises the question of market depth. In a 2021 paper, Adam Zaremba and others defined market breadth as the difference between rising and falling stocks. They stated market depth is a “robust predictor of future returns” in equity markets. According to Joe Mazzola, head trading and derivatives strategist at Charles Schwab, “Breadth is like a gauge of the market’s blood pressure. It gives you a sense of whether there’s strength or weakness. It’s a validating signal of sentiment that gives insight into how narrow or how broad participation is. The broader the participation, the stronger the signal.”

In other words, the state of the US market, especially after the recent rallies, signals one-sidedness. And analysts started raising the alarm as early as June. For instance, an S&P Global analysis in June stated that although the S&P 500 had recovered from the April decline, the “outsized returns of tech stocks” surfaced “concerns over a lack of market breadth.” The analysis cited Michael O’Rourke, chief market strategist at JonesTrading, who said: “I would not describe this rally as healthy.”

The analysis showed that the Magnificent Seven stocks had seen outsized gains since the April low. And any rally since then has been unimpressive when excluding these mega-cap tech stocks.

A month later, Reuters talked to analysts who raised the same issue. They warned that with so much riding on a handful of companies, any setbacks among them could ripple through markets. Michael Reynolds, VP of investment strategy at Glenmede, noted: “When a handful of stocks dominate the market … you could see disproportionate impacts … from just a handful of company-specific issues.” Lisa Shalett of Morgan Stanley Wealth added, “The biggest stocks are very expensive. If the biggest stocks fall the most, the index is very vulnerable.”

And the sentiments were prescient. The market was gripped by a sell-off soon after the market opened on August 29, which reached its nadir on September 2 at midday. Nasdaq led the decline, shedding 3.12% in that time. The broad market index pared 2.12%, while the Dow lost just 1.48%.

Overconcentration Raises Correction Risks

To put the current overconcentration into perspective, even at the height of the dot-com bubble, concentration levels hovered just around 30% (see the graphic below). But at nearly 40%, the top 10 companies’ share of the index now exceeds levels seen even during the dot-com bubble. Such concentration is not merely a historical anomaly, it directly affects market stability. As Ravi Kashyap’s research highlights, narrow leadership amplifies drawdown risk because index performance hinges disproportionately on a few names.

Source: Visual Capitalist

Source: Visual Capitalist

Put simply, when only a few big names are pulling the market up, it’s risky. If they falter, the entire index suffers, just as it did in the early 2000s. Today, we’re seeing a similar setup: a few large tech stocks are driving most of the gains. So if those leaders stumble, the market could drop sharply.

However, some argue that, yes, market concentration is high and valuations are elevated, but contend that speculative excess is milder than in the pre-dot-com era (around 1999). For instance, MSCI noted in a research note that today’s top-performing tech firms have higher profitability, robust revenue growth, and more reasonable valuations compared to their dot-com counterparts. This is a stance that Cambridge Associates supports, stating that IT sector operating margins now average 23.7%, versus just 13.6% in 1998–1999. Balance sheets are also healthier, according to Cambridge Associates, which notes that companies today cover interest expenses with operating cash flow at a 9.6x ratio, compared to 5.3x in the late 1990s.

Granted, the current market bears several similarities to the dot-com era, most notably in concentration and elevated valuations. Nevertheless, the underlying fundamentals today are markedly stronger. Speculative excess appears more contained, supported by healthier balance sheets and more resilient earnings. Risk is there, but its nature is different; it is less about exuberance, more about structural exposure.

Conclusion

What this means is that the ongoing pause in the rally is not a healthy one. Instead, these are signs of structural stress. According to Business Insider’s Samuel O’Brient, tech stocks are “getting whacked” due to a trifecta of headwinds: surging bond yields, Fed independence concerns, and tariff uncertainty. These aren’t typical catalysts for a short-term breather; they point to a deeper macro instability. On the other hand, Doug Busch, a senior technical analyst at Barron’s, warned that September is historically tough for stocks, and this year, tech is especially vulnerable. The sell-off is not just profit-taking; it’s a reaction to elevated valuations and fragile leadership.

But the pause is also not (yet) the start of a deeper correction. Despite the tech slump, major indexes are still hovering near record levels. In fact, the S&P 500 closed at 6,415.54 on September 2, down 1.33% from the August 28 peak and up 0.81% for the day; this is hardly a capitulation. Add to that Google’s partial win in its antitrust case, which some see as a positive for Big Tech, and that it could support a tech rebound.

Neha Gupta

Neha Gupta is a Chartered Financial Analyst with over 18 years of experience in finance and more than 11 years as a financial writer. She’s authored for clients worldwide, including platforms like MarketWatch, TipRanks, InsiderMonkey, and Seeking Alpha. Her work is known for its technical rigor, clear communication, and compliance-awareness—evident in her success enhancing market updates.